Where is the Paris Bible today?

Thousands of Paris Bibles have been created between the 13th and the 14th centuries, making them one of the most important kinds of manuscripts produced in the medieval period along with Books of Hours and an ideal object for scaled, computational research (Boillet et al, 2019). There are many uncertainties about studying this material as data. First of all, it is difficult to say with certainty from catalog records alone (in the absence of digitization) if a manuscript from the period listed as a “Bible” is, in fact, of the sort we have described as a Paris Bible (see Blogpost 1). Second, as with most medieval collections, dating and localization of the manuscripts are notoriously complex. It would be a rare manuscript that gives a precise indication of where and when it was produced. Third, it is difficult to estimate what percentage of Paris Bibles is preserved today, although recent approaches in species modeling might provide some interesting hypotheses (Kestemont and Karsdorp). One thing we can say with certainty is where the identified Bibles are currently located.

Figure 1: A labelled map of concentrations of Paris Bibles held in library collections around the world as of the PBP database on 16 June 2021. Map made in QGIS with an OpenStreetMap base. See this image here.

Our dataset of Paris Bibles in global collections has a little more than 300 entries at the time of writing this post. Since “current location” is usually an unambiguous metadata field, it is easy to map these 300+ Paris Bibles. With our current numbers, it is easy to see that the highest concentration of such digitized Bibles in the world can be found in New York City, Philadelphia, Madrid, Rome, Paris and Copenhagen. The numbers will, without a doubt, change over time as our database grows and becomes more inclusive.

In her thesis Ruzzier (2010) has compiled a database of 1800 known portable Bibles. It has not yet been published, but we too have begun compiling a list of digitized copies of Bibles which we have made available in a repository of the Paris Bible Project’s Github. Ruzzier first raised the question of the disparity between cataloging practices and extant manuscripts: the United States, France or England have good and mostly digitised catalogues. We have found, for example, the Lewis collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia to have quite a representative sample of time period and regions of production, albeit within a specific history of North American collections. With Ruzzier we believe that there are probably many more Paris Bibles to be found in Italy and Spain, particularly in the small libraries and private collections. Since dozens of Paris Bibles have been, and continue to be, auctioned or sold privately every year, the Schoenberg database may be of particular help with this last point (SIMS, 2021).

In the same way the Paris Bible model spread around Europe in the Middle Ages with every student, professor or friar wanting their own exemplar, public institutions or private collectors interested in manuscripts in the twentieth and twenty-first century strove to have a copy of their own. We can trace them in hundreds of collections all around the world.

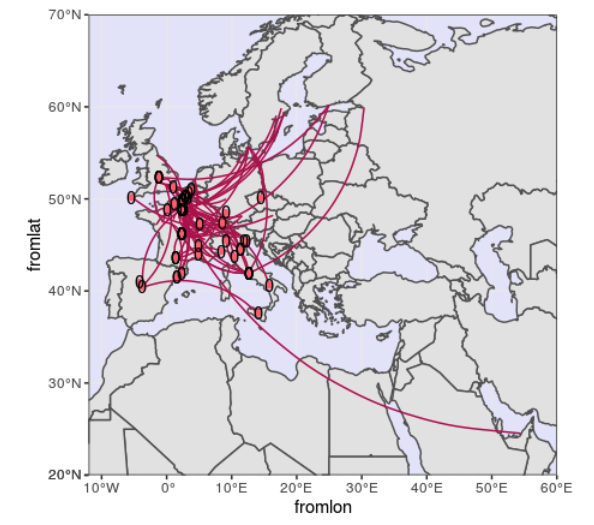

Using localization information given by library catalogs or other digital resources to build a map is a much trickier endeavor. First of all, indications of a location of where a manuscript was copied or from where a manuscript originated are notoriously imprecise both in terms of the certainty and granularity of the data. We find location information in catalog descriptions such as “Paris or N France?,” “Rouen region,” “library of the Dominican friars of Clermont-Ferrand,” “France or England,” or even “unknown.” In order to build a map such as the one in Figure 2, we removed examples of Paris Bibles where the place of fabrication and current location were very close (say within a few kilometers of each other). If records contained a “?” this was resolved to certainty and regional descriptors such as “Northern France” were resolved to a representative city for the purposes of automatic geocoding. A map, such as the one in Figure 2, is more of a suggestion of general patterns in the dataset about the origin and current than it is a representation of certainty and it should be considered accordingly.

Figure 2: A point-to-point map suggesting some trajectories of Paris Bibles from their hypothesized place of fabrication to their known current location. The red ovals are places of fabrication. Map built in R using ggplot2 with code adapted from Prevos. See this image here.

One of our project’s goals is to publish our data and metadata openly with clear reuse licenses and to develop interesting ways of visualizing and interacting with that data. We also invite everyone interested to contribute to this research to share their knowledge. Our list of Paris Bible is a work in progress that extends through geographies and times. It is accessible on Github, at this address: https://github.com/parisbible/mss.

Anyone having information about Paris Bibles that we do not have a record of, digitized or not, in public or public collections, is encouraged to contact us, either by sending us a pull request with corrected data or by consulting our multilingual Participate page that gives the specific information we are interested in collecting.

Estelle Guéville, David Joseph Wrisley, and Niccolò Acram Cappelletto

Sources:

Boillet, Mélodie, Bonhomme, Marie-Laurence, Stutzmann, Dominique, Kermorvant, Christopher. (2019). HORAE: an annotated dataset of books of hours. In Proceedings of The 5th International Workshop on Historical Document Imaging and Processing, Sydney, NSW, Australia, September 20–21, 2019 (HIP’19), DOI: 10.1145/3352631.3352633.

- Kestemont, Mike and Karsdorp, Folgert. (2020). Estimating The Loss of Medieval Literature With an Unseen Species Model from Ecodiversity. CHR 2020: Workshop on Computational Humanities Research, November 18–20, 2020, Amsterdam. 44-55.

- Prevos, Peter. (2017) “Create Air Travel Route Maps in ggplot: A Visual Travel Diary”.

- Ruzzier, Chiara. (2018). ‘Les manuscrits de la Bible au XIIIe siècle: quelques aspects de la réception du modèle parisien dans l’Europe méridionale’, in Medieval Europe in Motion: The Circulation of Artists, Images, Patterns and Ideas from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Coast (6th-15th centuries). Bilotta, M. A. (ed.). Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali, 281-297

- Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies. (2021). Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts.

Suggested citation

Cappelletto, Niccolò Acram, Guéville, Estelle, and Wrisley, David Joseph. (22 June 2021). Where is the Paris Bible today? Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.