What is a Paris Bible?

The birth and spread of a new model

Up until the beginning of the thirteenth century, manuscripts were mostly produced in workshops attached to the court or by monks in monasteries. These latter workshops, called scriptoria (literally - scriptorium - “a place for writing”) produced a large number of manuscripts, both masterpieces and “ordinary” ones, dedicated to study, reading and teaching. However, in the second half of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th century, the creation of Universities, the first of them being the University of Paris (1150), greatly influenced the production of manuscripts, bibles in particular. The revision of the Christian scriptures around 1220 resulted in a corrected text, with books following one another in a standard order, introduced by prologues and divided into chapters. This is the template upon which the structure of the modern bible is based and we usually call them Paris Bibles (or Parisian Bibles).

The production of these Bibles has been linked to the rise of literacy and, as Sabina Magrini (2007, p. 222) has argued: “their existence and diffusion bear witness to the new relationship developed between the book and its reader, ecclesiastical or layman, scholar or devout alike”.

Laura Light (2012) has written:

For the first time in the Middle Ages, the Bible became a book owned and used by individuals, ranging from the students and masters of the new and rapidly growing universities, to the bishops and priests of a church that was emphasising its pastoral role as never before, to the wandering preachers of the Franciscan and Dominican orders.

The book in this period was intended for individual, rather than institutional, use and the growing production from the 13th century onwards might be understood as a response to a specific phenomenon which lasted for centuries: a growing number of people needing books (Ornato, 1985, p. 59). The result of this production is thousands of manuscripts across mountains and seas in Europe, a large part of which is extant in public collections, albeit often undigitized.

In other words, the Paris Bible is a codex made in a certain style, not necessarily a Bible made in Paris.

Revising the uniformity thesis

As a new model that spread around Europe for a period lasting at least two centuries, these Bibles share a number of codicological, paleographic and aesthetic features often cited by the scholarly community as defining features of Paris Bibles:

The use of senions (313.07), a quire organization replacing the quaternions (313.05) which were widely used in the previous periods.

The Biblical texts are preceded by prologues and the full text ends with the Interpretation of Hebrew Names.

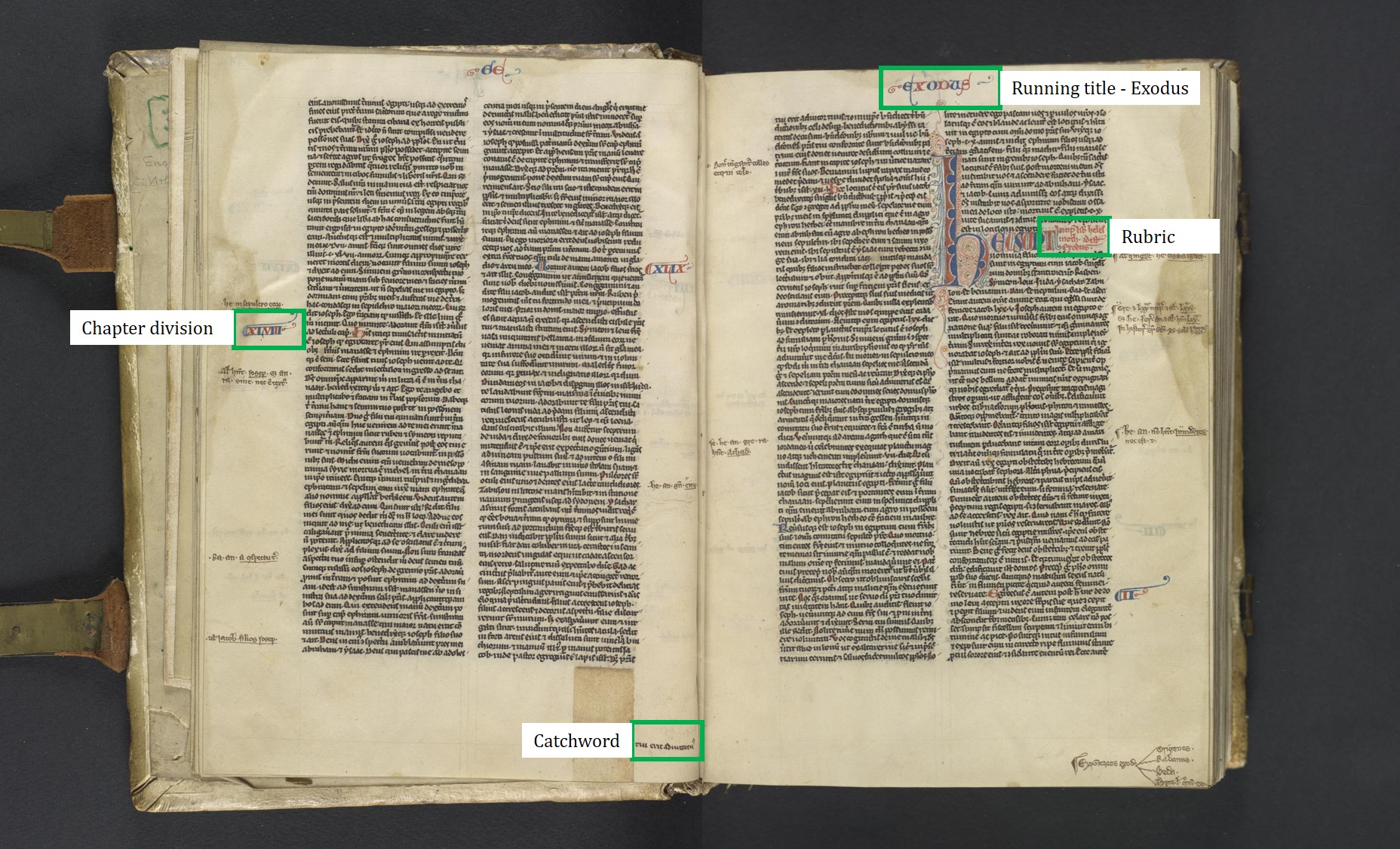

The development of a “tracking system” with the presence of “running titles” on top of each page as well as rubrics (333.01), signatures (423.03), catchwords (333.09), etc.

Mostly pandects, meaning one-volume Bibles even though few two volumes bibles such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi Bible (2013.051), University of Pennsylvania Ms 1053 or Burgerbibliothek Bern Hs 27/28 are extant. Before the advent of the Paris Bible, bibles were bound in several volumes, usually at least 3 or 4.

The establishment of a new division of the chapters and biblical books, which follow scrupulously the same order. In previous periods, the order of the books followed the liturgy and changed from one Bible to another.

An increased number of abbreviations added to a smaller font size and more lines on the pages (ranging generally between 40 to 60) with a division in two text columns.

Paris bibles use the Vulgate text from Saint Jerome.

They were commercially produced, often with no particular owner in mind, contrary to a more patron-driven system of manuscript production.

Finally, these many shared features have led scholars to consider them as aesthetically uniform.

© Free Library of Philadelphia, ms. Lewis E31, ff. 14v-15r.

If we look more closely at the materiality of Paris Bibles we have found that manuscripts exhibit many differences, casting doubt on the question of their uniformity. As an example, we found echoes of the Vetus Latina as well as patristic texts in our transcriptions (Guéville and Wrisley, 2020). Below are a few examples of this variance. At left is the normalized text of the Vulgate. In the center columns, you will find the text from one such bible manuscript in our transcription system. At right, there is a corresponding citation from the Old Latin Bible from the sermoning tradition (VLB-O, 2021).

| Vulgate Gen 1: 12 | Smith-Lesouëf 19 | Venerable Bede |

|---|---|---|

| Et protulit terra herbam virentem, et facientem semen juxta genus suum, | Et ꝓtulit t́ra herbam uirentem ⁊ afferentē ſemē iuxta genuſ ſuū | Et protulit terra herbam virentem, et afferentem semen juxta genus suum, |

| Vulgate | LAD 2013.051 (Genesis) | VLB-O (Brepols) |

|---|---|---|

| et recordabor fœderis mei vobiscum, et cum omni anima vivente quæ carnem vegetat | Et recoꝛꝺaboꝛ feꝺeriſ mei ꝙ pepigi uob́cum ⁊ cum om̄i animauiuente que carnem uegetat | et recordabor foederis mei, quod pepigi vobiscum (PS-EUCH) |

| Dixitque ei angelus Domini: Revertere ad dominam tuam, et humiliare sub manu illius. | Dixitqꝫ ei angĺs ꝺomini. Reút́e aꝺ ꝺominam tuam ⁊ humilia-re ſub manu ip̄ius | Dixitque angelus Domini Revertere ad dominam tuam, et humiliare sub manu ipsius. (PS-EUCH) |

| Vimque faciebant Lot vehementissime: jamque prope erat ut effringerent fores. | Uimqꝫ faciebant loth uehem̄tiſſime iam ꝓpe erat ut **īſtrīǵent **foꝛes. | Vimque faciebant Lot vehementissime: jamque prope erat ut infringerent fores. (PS-EUCH) |

| duodecim duces generabit, et faciam illum in gentem magnam. | xii. ꝺuces genera-bit ⁊ faciā illū creſcere in gentē magnam. | duodecim duces generabit et faciam illum crescere in gentem magnum(BREV GOTH) |

| Leva oculos tuos et vide a loco, in quo nunc es, ad aquilonem et meridiem, ad orientem et occidentem. | Leua oculos tuos ī ꝺirectū⁊ uiꝺe a loco ī quo nunc eſ aꝺ a-quilonē ⁊ ḿiꝺiem aꝺ oꝛientem⁊ occidentem. | Leua oculos tuos in directum et uide a loco in quo nunc es, ad aquilonem et meridiem et orientem et occidentem. (Nicolas de Aquavilla) |

These traces of a pre-Vulgate text we have found by matching phrases in the Vetus Latin Bible Online database are probably not the only time that Biblical text varies, and they suggest a milieu in which scribal practices and literacies find their way into the Paris Bible copy, suggesting fluidity and variance in textual production rather than uniformity.

Some manuscripts recognised as Paris Bibles can also change slightly the order of the biblical books. For example, in our corpus, University of Pennsylvania, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Ms. Codex 1065, a mid-thirteenth century Paris Bible of yet unknown origin, has the Interpretations of the Hebrew names following the Psalms instead of being at the end of the manuscript.

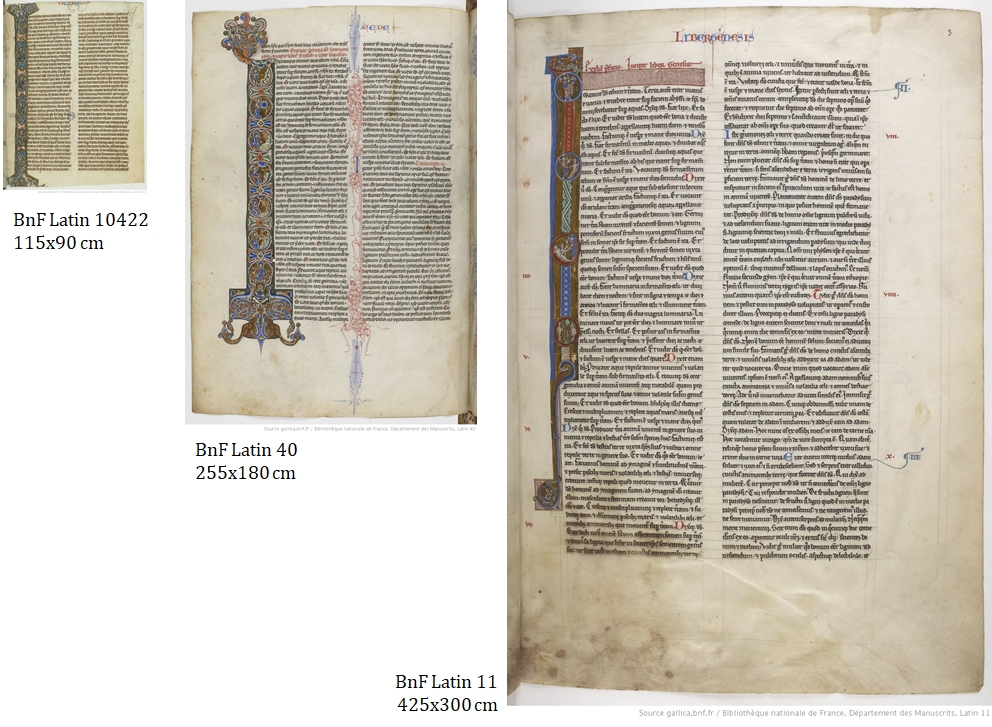

When we ask the question “Are the bibles aesthetically uniform?”, a cursory glance at the manuscripts shows how they can be similar, given the layout of the page, including the two columns, running titles and other features, but they are clearly not uniform. The decoration, the size of the manuscript and even the script and frequency of abbreviation vary significantly from one manuscript to another.

When size matters

Pocket Bibles and Paris Bibles are often confused for one another because they indeed share a lot of common features. The major difference lays in the size of these manuscripts. Ruzzier (2018) created three groups to distinguish these bibles: the first one, described as “pocket bibles” with a size she defines as the height added to the width, the total dimensions coming to under 380mm, the second one with a size under 550mm and the last one with a size above 550mm.

© Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

The pocket Bible might be best understood as the evolution of the Paris Bible, a smaller version of it, made possible thanks to the evolution of technologies of bookmaking, including the creation of better materials, smaller script, and intensive use of abbreviations allowing an increased miniaturization (Ruzzier 118, 120). The pocket Bible had to be small enough to be carried for travel purposes, particularly in the context of preaching and the evangelistic mission of the friars. In summary, pocket Bibles are Paris Bibles whereas not all Paris Bibles are Pocket Bibles. One of the main aims of the Paris Bible Project will be to assemble an open dataset of metadata from Paris Bibles found in global collections, not only about the materiality and hypothesized provenance of the bibles, but also from the non-normalized text of the individual documents, in order to shine further light on the complexity of the history of the development and diffusion of Paris Bibles in medieval Europe.

Estelle Guéville and David Joseph Wrisley

Sources

- Brepols Vetus Latin Bible Online (VLB-O). (2021).

- D’Esneval, Amaury. (1978). La division de la vulgate latine en chapitres dans l’édition parisienne du XIIIe siècle. Revue des Sciences philosophiques et théologiques, 62(4), 559-568.

- Guéville, Estelle, and Wrisley, David Joseph. (2020, September 9). Rethinking the Abbreviation: questions and challenges of machine reading medieval scripta. Dark Archives 20/20.

- Light, Laura. (1994). French Bibles c. 1200-30: a new look at the origin of the Paris Bible. In R. Gameson (Ed.). The Early Medieval Bible: Its production, decoration and use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Light, Laura. (2012). The Thirteenth-Century Bible: The Paris Bible and Beyond. In R. Marsden and E. A. Matter (Eds). The New Cambridge History of the Bible. Volume two, c. 600-1450. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lobrichon, Guy. (2003). La Bible au Moyen Age. Paris: Picard.

- Magrini, Sabina. (2005). La Bibbia all’Università (Secoli XII-XIV): La ‘Bible de Paris’ e la sua Influenza sulla Produzione Scritturale Coeva. In Cherubini, P. (Ed.) Forme e Modelli della Tradizione Manoscritta della Bibbia (pp. 407-421). Città del Vaticano: Scuola Vaticana di Paleografia, Diplomatica e Archivistica.

- Muzerelle, Denis. (1985). Vocabulaire codicologique : répertoire méthodique des termes français relatifs aux manuscrits. Paris : Editions CEMI.

- Ornato, Ezio. (1985). ‘Les conditions de production et de diffusion du livre médiéval (XIIIe-XVe siècles). Quelques considérations générales’. In: Culture et idéologie dans la genèse de l’État moderne. Actes de la table ronde de Rome (15-17 octobre 1984) Rome : École Française de Rome. pp. 57-84. (Publications de l’École française de Rome, 82).

- Ruzzier, Chiara. (2010). Entre universités et ordres mendiants. La Miniaturisation de la Bible au XIIIe siècle. PhD Thesis. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris.

- Ruzzier, Chiara. (2016). ‘Des armaria aux besaces: La mutation de la Bible au XIIIe siècle’, in Le Moyen Âge dans le texte. Cinq ans d’histoire textuelle au Laboratoire de médiévistique occidentale de Paris. Grevin, B. & Mairey, A. (eds.). Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, p. 73-111 38 p.

- Ruzzier, C. (2018). Les manuscrits de la Bible au XIIIe siècle: quelques aspects de la réception du modèle parisien dans l’Europe méridionale. In M. A. Bilotta (Ed.), Medieval Europe in Motion: The Circulation of Artists, Images, Patterns and Ideas from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Coast (6th-15th centuries) (p. 281-297). Officina di Studi Medievali.

You can also consult the bibliography of the project on Zotero.

Suggested citation

Guéville, Estelle and Wrisley, David Joseph. (15 June 2021). What is a Paris Bible? Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.