Bible hunting: where to find data? The case of Switzerland and e-codices.

Speaking from experience, there always comes a time in anyone’s academic career when you feel like pulling your hair out because a search engine let you down, again. And in that moment, you truly feel as if the gods of the internet are not listening to you, or straight up ignoring you. For the medievalist (and, to a larger extent, anyone whose job rests on the availability of priceless items through the good old web), that struggle is often only too real.

Manuscript hunting in Switzerland, however, is made incredibly easy by the online platform e-codices, where manuscripts from all regions of the country are compiled in one place to facilitate research and access to material that would otherwise have sat on dusty bookshelves, largely forgotten by the wider public (medievalists, archivists and librarians don’t count, dusty bookshelves are their usual stomping ground).

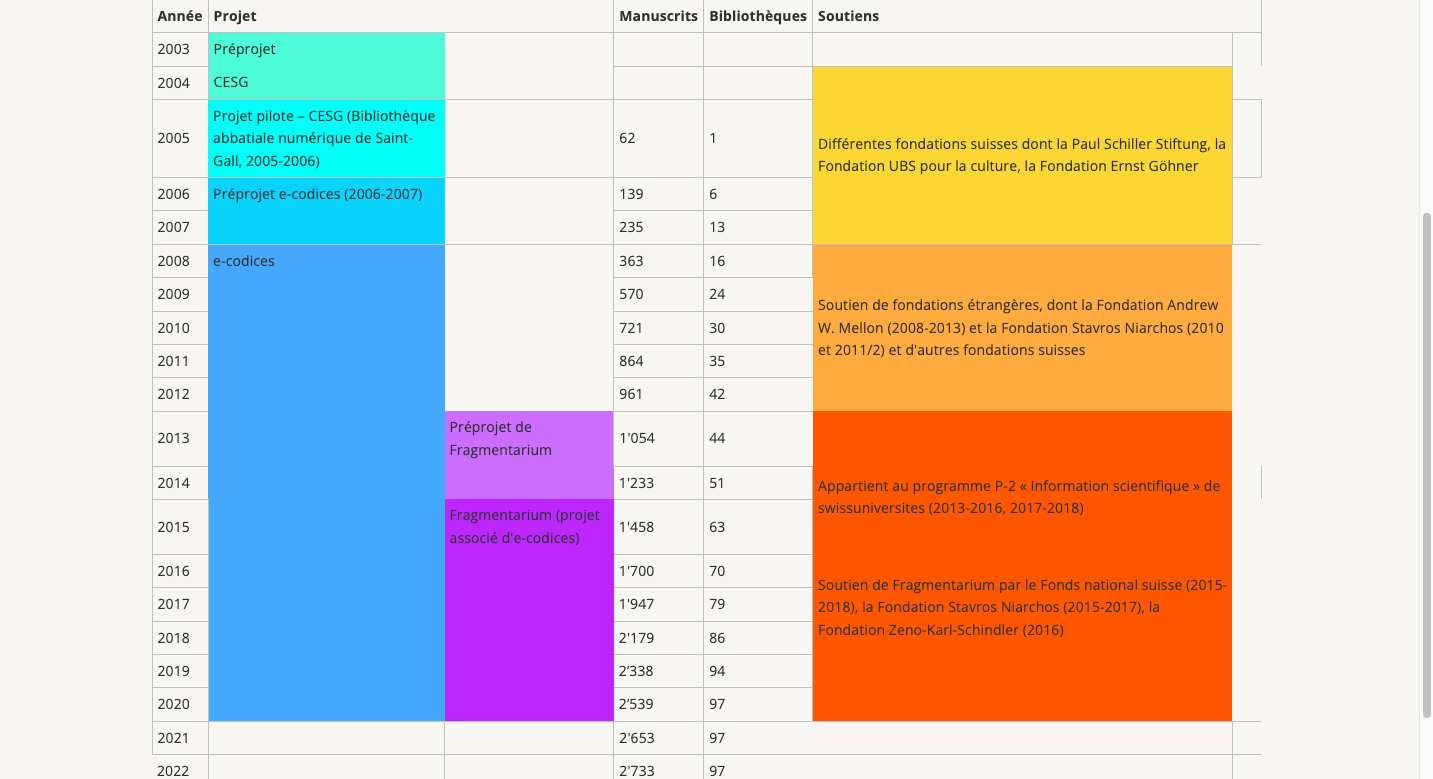

The platform e-codices, originally founded in the early 2000s, “offers free online access to medieval and early modern manuscripts from public and church-owned collections as well as from numerous private collections” (check out their “Brief History” snippet). It is, in short, the virtual manuscript library of Switzerland. And that’s not nothing!

Considering the interface is built to give information in three different languages, for all its manuscripts, its inherent multilingualism strives to help further research and facilitate access and understanding of the manuscripts hosted by the platform. An undertaking of some magnitude, since, by January of 2021, e-codices boasted of an impressive 3,270 digitized manuscripts in its collection.

Now, of course, when compared to the much larger platforms, such as Gallica for example, that may not seem all that impressive, but let’s not forget that all of the digitizations present on e-codices are of the highest quality, a definite bonus for the desperate medievalist in search of not only content, but good content. If you’re curious about how e-codices what material is used to digitize content for the platform, you can head to their “Reproductions Guidelines” to learn more!

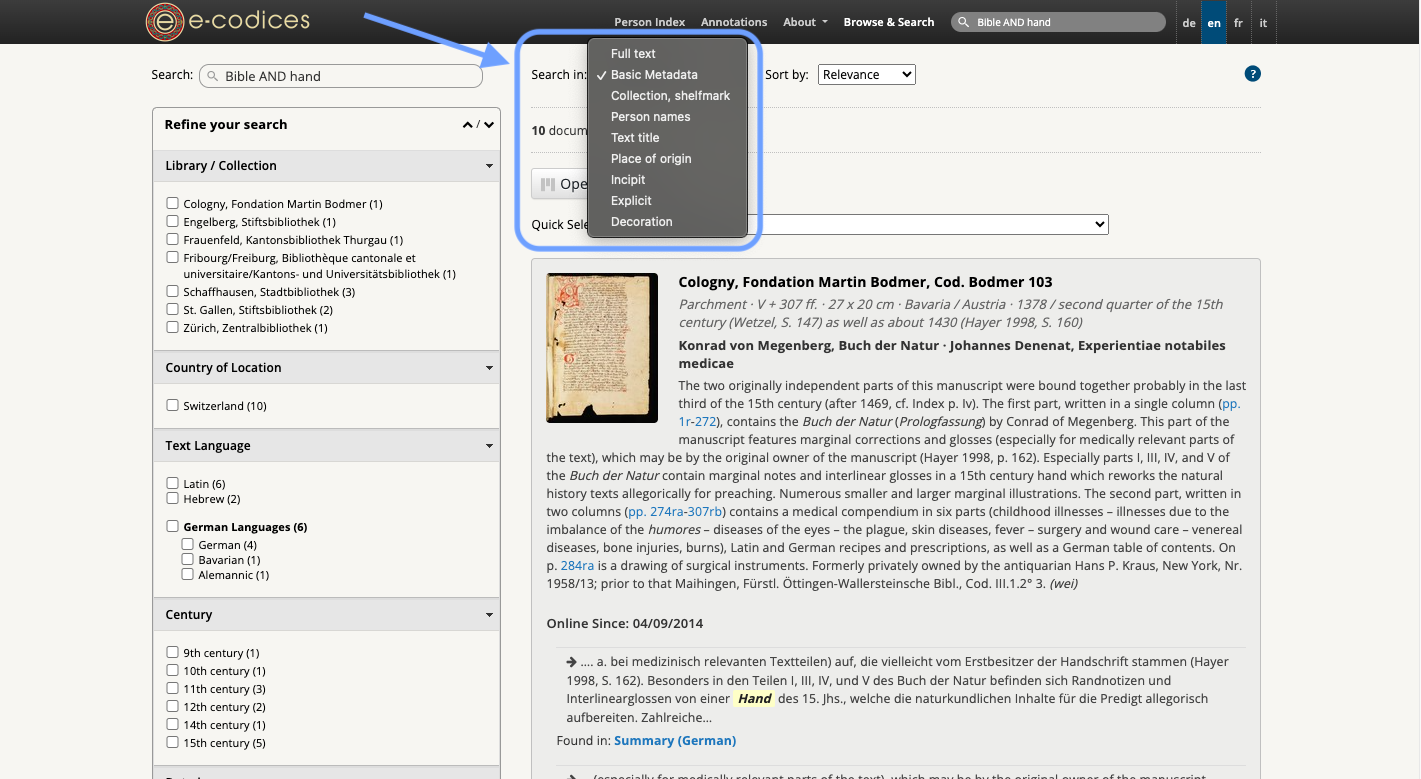

It’s simple enough to find whatever it is that you’re looking for within the vast metadata jungle of the platform since the system does it for you. All you need is to know precisely what it is you’re looking for. For example, in the context of the Paris Bible Project, we’re looking for evidence of scribal differences in Parisian Bibles. So, in the search bar, I would use a simple string search by typing in the following combinations: “Bible AND hand”, “Bible AND scribe” or “Bible AND hands” (don’t forget the plural, sometimes it yields interesting results!).

You can either choose to limit your research to the basic metadata (which, in this instance, I would recommend) or opt for the full-text search, which is essentially what happens when you use Gallica, for example, and might yield a ton of results, but not necessarily the ones you want. Hence the importance of super precise metadata, but that’s a subject for another time.

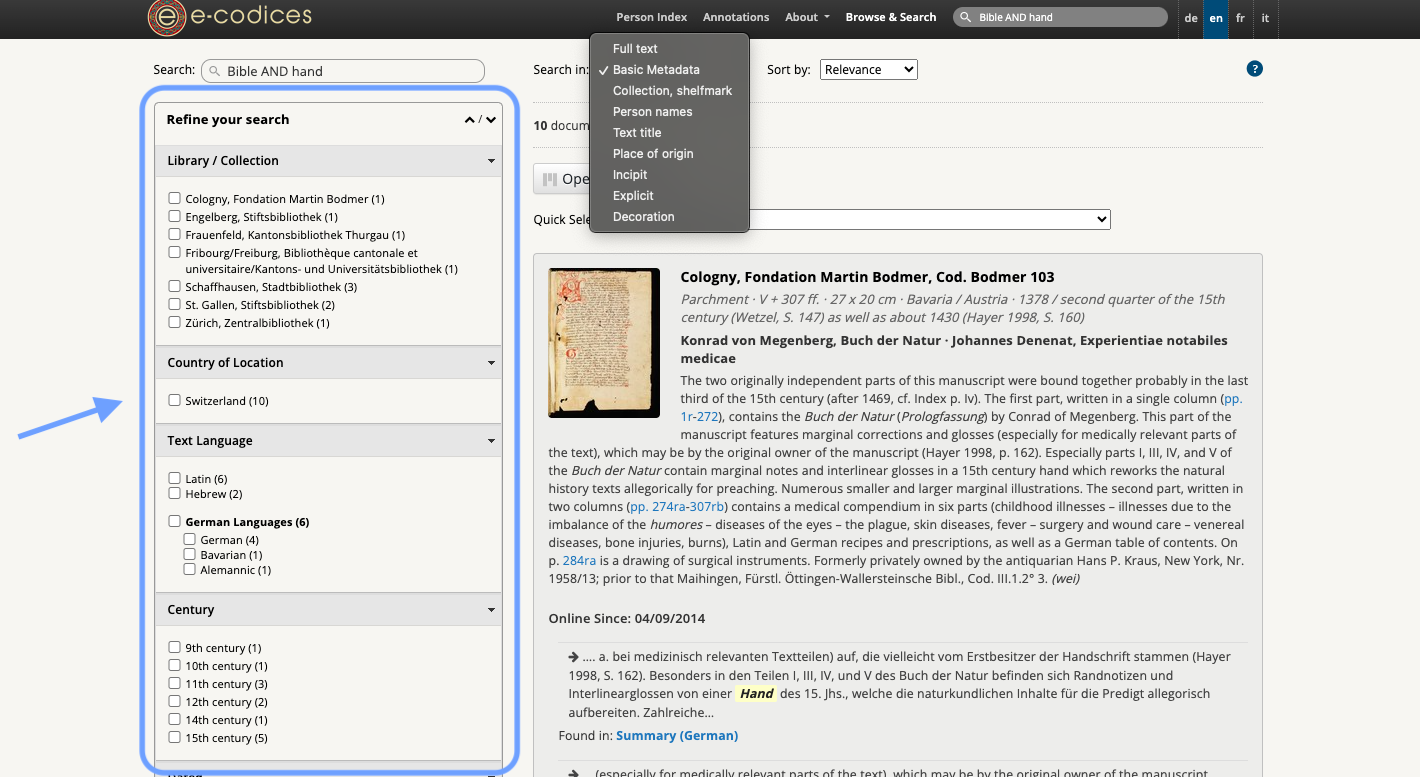

Then, it’s just a question of filtering out the search results you don’t need. In our case, I’d usually filter by date, since Parisian Bibles were produced in somewhat of a definite timeline (although that’s also up for debate amongst medievalists). I would probably select a branch of time between the second half of the 12th century and the end of the 15th, to allow for any stragglers or early bloomers.

But you could also, depending on your own research and your own criteria, filter by language. In the case of the Paris Bible Project, we focus mainly on Latin manuscripts, so anything else, no matter how interesting, gets sidelined–either permanently or, if we come across a particularly interesting manuscript, for future research. Who knows? Don’t discard interesting search results just because they don’t fit one of your criteria, you might still find something super cool that nobody has really researched before! It really all depends on how much time you have.

The screenshots show only a tiny fraction of e-codices’ truly quite phenomenal search engine. You have tons of other options! You can choose to filter according to other specialized criteria, such as: does the manuscript you’re looking for have annotations? Are you interested in decorations, or more of a text-based researcher? What kind of decorations? Has the manuscript been restored or not? Depending on your timeline, you may get more or less options in either of these filters, but it’s still worth exploring.

In the context of our own project, however, I would then look at the manuscript itself to see whether or not it fits the criteria of a Paris Bible (see blog post “What is a Paris Bible?” for reference). Does it look like one? What about the codicological aspect? Sometimes, you get lucky and you get a very precise, extremely detailed description… and sometimes not so much. If you’re unlucky, you might have to channel your inner Sherlock Holmes and do a bit of sleuthing to try and dig up older catalog editions.

If you have additional suggestions for exploring collections in Switzerland not covered here or additional tips, drop us a line at parisbible(at)gmail(dot)com.

Alice Fournier

Suggested citation

Fournier, Alice. (16 March 2024). Bible hunting: where to find data? The case of Switzerland and e-codices. Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.