PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon #7: the case of Beinecke ZZi 56

Paris Bible Correct-a-thon Besançon: Beinecke ZZi 56

Introduction

This blogpost was written in the context of the Paris Bible Challenge which took place in Besançon, France in January 2023.

It focuses on discussing some common mistakes made by Transkribus in its attempts to automatically transcribe the bible known as Beinecke ZZi 56. We also share our impressions of contributing to this preliminary stage of the overall challenge.

The Gutenberg Bible

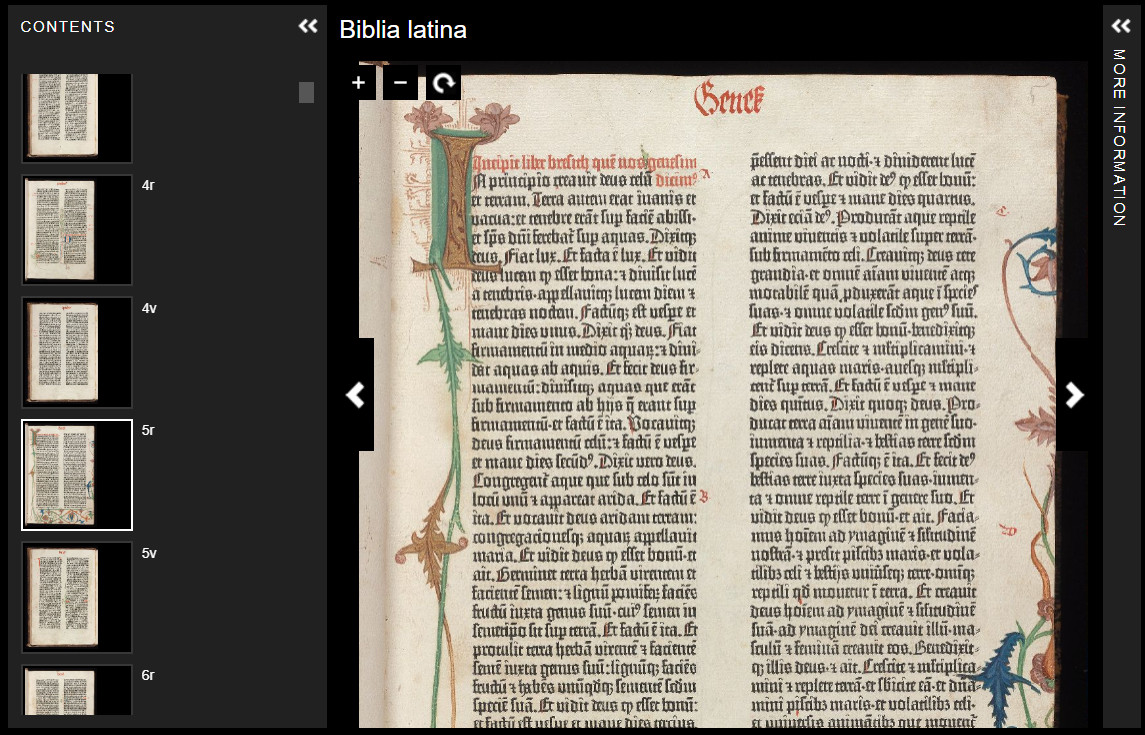

The document we worked on is the digitized version of the Gutenberg Bible(https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2020598), printed in Mainz around 1454. Beinecke ZZi 56 is unique in the PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon as it is the only printed text that was used. This meant that our correction process was different to that of other groups who were correcting the output from manuscript texts.

The printing of this Bible followed smaller works that enabled Gutenberg to gain both printing experience and the courage to embark on such a huge project. This book is considered as a typographical monument due to the black letter types cast for its production, the length of the work and its features. The book has 641 folio leaves and twice that number of pages. It was originally intended to be bound in two volumes (Keogh, 1926). It has neither pagination nor foliation, and is therefore difficult to collate, except by comparing one copy with another.

Fig.1. Biblia Latina Leaf with Decorated Initial.” Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Digital Collections. Yale University Library. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2020598.

This bible uses abbreviations in its printed version, although it is not clear if there is a model from which these abbreviations were derived. We posited that the abbreviations that appear in the text would follow a similar pattern and deployment scheme overall, as the whole Bible was printed using premade type characters. We assumed this would thus limit the internal variations that could appear, as opposed to the natural and more fluid variation produced by the human hand, especially when multiple scribes are involved. This was largely a correct hypothesis; however we found that the mistakes made by the Transkribus model also tended to be repeated with certain combinations of types.

From the perspective of the challenge, using a printed Bible also meant that deciphering the words and distinguishing abbreviations was a relatively simpler process than that of our classmates. As printed text does not vary as much as handwritten text does, this made our task easier as we advanced with our correction.

Common Findings:

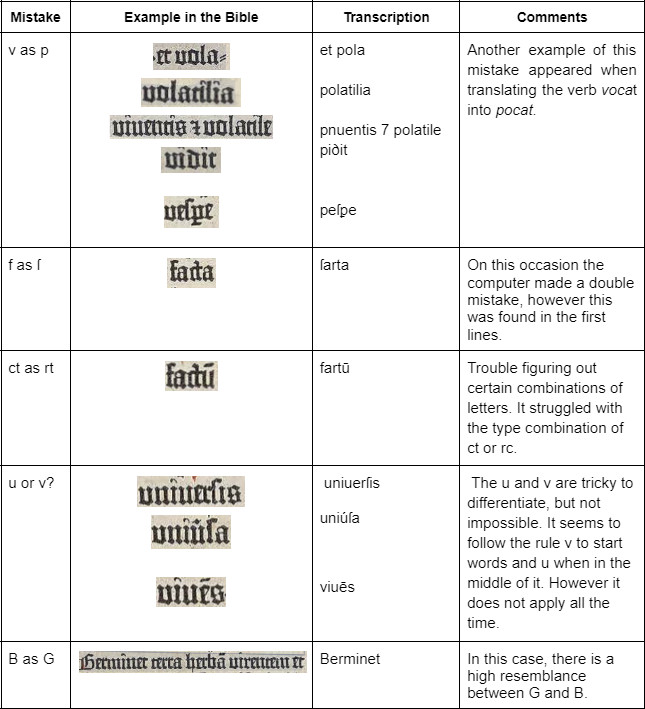

As mentioned above, we found that the correction process for transcriptions made by Transkribus was generally easier with a printed text that was designed to resemble human handwriting, as the Gutenberg Bible was intended to do and indeed all incunabula were. However, with machine learning there is always the risk of overfitting, which in our case created some peculiar, surprising and recurrent errors during the automatic transcription, as the machine tried to apply the ground truth as harvested from other handwritten Paris bibles.

Overfitting occurs when a model’s parameters and hyperparameters are optimized to get the best possible performance on the training data. By optimizing for error on the training data and ignoring how a model will perform outside of that sample, a machine learning model will have excellent performance on the training data and poor performance on new data. (Lofgreen, 2019). The following examples are some of the most frequent mistakes made by the automatic transcription in the first two pages of the book of Genesis.

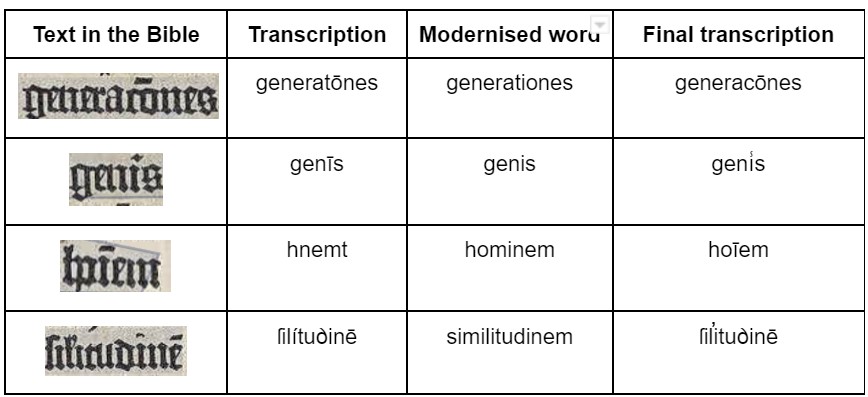

Concerning the abbreviations used in the text, the table below details another set of mistakes that were more difficult to classify and correct due to the nature of their representation. There were times during the process where we naturally started to focus more on reading and deciphering the words as humans and we forgot our main task was not to modernise the transcription for contemporary readers, but rather to enable the machine to identify what appeared in the text and create a representation of this. This created a certain degree of debate between us to reach an agreement on how the text should be transcribed, especially when we were had the modern version of Genesis beside us as we worked and we were limited by the use of special characters which had been pre-loaded into the Transkribus virtual keyboard.

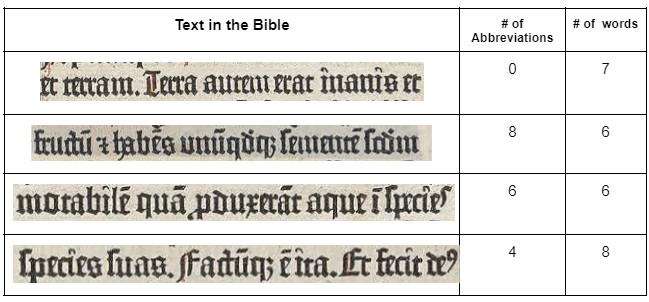

Abbreviations

The use of abbreviations seems to have been a system of symbols employed to save time and space when copying texts by hand in manuscript. The efficiency of the system made its way into the movable type at the beginning of the print revolution as another efficient way to produce books. This not only reduced the variability in style that could be found in manuscripts by standardizing the forms, it also reduced the price of producing a book. However, the real matter about the use of abbreviations in Latin manuscripts and printed text seems to be more connected to ‘when’ rather than ‘how’ they are implemented in the text. It is evident that each symbol has a phonetic equivalent that is used to replace either letter combinations, endings or letters that occupy two spaces such as “m” but those uses are not a rule to be applied at all times, as there are several exceptions and situations where an abbreviation is placed in the text which makes difficult to define a pattern or explain their recurrency.

The following table displays how random the abbreviations used can actually be in different lines of text as compared with the number of words in the line.

ꝺeus et ꝺeꝰ

Visualisation of the most used terms in the first two transcribed pages of Genesis.

Further Research Centers

Further research must be carried out to provide more insight to this subject. Is the use of abbreviations linked to an attempt to maintain the proportions of the original manuscripts Bibles (exemplar)? Was there an exemplar on which this Gutenberg Bible was modeled? Could the comparison of the use of abbreviations allow/help the identification of the exemplar? Did abbreviations correspond to an interest in reducing the costs of materials? Or were they simply a decorative feature? Does the particular hand of the Gutenberg correspond to specific manuscripts or is it an idealized version thereof?

Despite the misinterpretations made by Transkribus in representing certain abbreviations, the outcome provided by this AI has already proven it to be a powerful tool. We can thus begin to see the full reach of this tool on the humanities field and its scope in illuminating new centers of focus for research.

Finally, participating in a community challenge such as this one was a valuable experience that allowed us to engage with current academic projects and be involved in on-going research.

Further reading

- Keogh, A. (1926). The Gutenberg Bible as a Typographical Monument. The Yale University Library Gazette, 1(1). http://www.jstor.org/stable/40856598

- Lofgreen, A. (2019). [Overfitting: What to Do When Your Model Is Synced Too Closely to Your Training Data] (https://www.datarobot.com/blog/overfitting-what-to-do-when-your-model-is-synced-too-closely-to-your-training-data/) </ul>

## Team Úna Faller, Diego Rodriguez. ## **Suggested citation** Faller, Úna and Rodriguez, Diego. (29 June 2023). Paris Bible Correct-a-thon Besançon: Beinecke ZZi 56. *Paris Bible Project.* https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632 This post is published with a [CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).