PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon #6: the case of Aargauer Kantonsbibliothek, MsWettF 11

PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon: Aargauer Kantonsbibliothek, MsWettF 11

This blogpost was written in the context of the Paris Bible Challenge which took place in Besançon, France in January 2023.

During this project, we’ve used the transcriptions created by the HTR engine Transkribus to explore medieval bibles. In order to be able to decipher, and to correct, these transcriptions, we have used an online edition of the Vulgate of the book of Genesis. Dealing with difficult abbreviations was an interesting part of the correct-a-thon.

Physical description of MsWettF 11

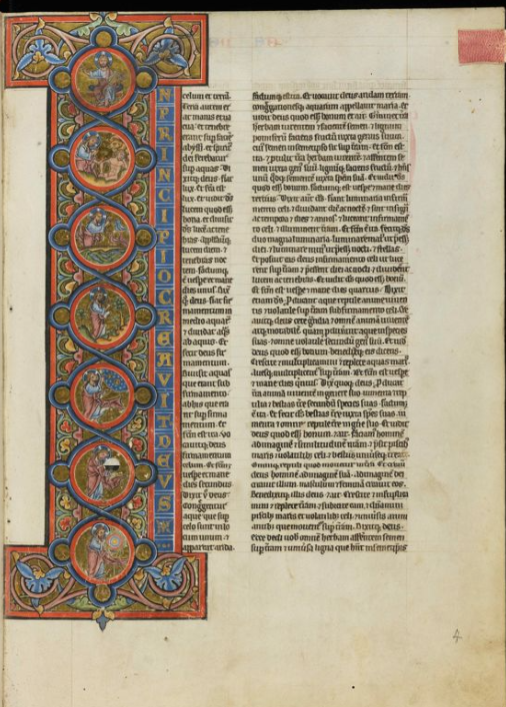

The Paris bible is a kind of medieval Latin Bible that was diffused throughout Europe beginning in the thirteenth century. We worked with the codex known as Aarau, Aargauer Kantonsbibliothek MsWettF 11 which was written in Germany in the third quarter of the 13th century. It is medium sized [315 x 225 mm], and is composed of 833 parchment folios. The headings and titles are drawn with stylized majuscule letters and abbreviated expressions, including distinguishable coloring, gold adornments, and sketches. The bible is held the Aargauer Kantonsbibliothek in Switzerland .

The first initial of Genesis narrates the creation of the universal in seven circles. The story of the creation of life, animals, and human beings are found in each circle

Figure 1: Genesis, page 7

Transkribus

Although, we have been studying Latin, this correct-a-thon has been our first adventure working with a medieval Latin manuscript with Transkribus. The copyists’ Gothic script was fascinating for us, but deciphering it was the most challenging part. Seen from this perspective, Transkribus is incredibly useful. We had not before witnessed an HTR engine recognize a highly abbreviated Gothic style medieval Bible text with so few errors. Using the knowledge that the existing medieval Latin model of the Paris Bible Project contained, we were able to save a lot of time, focusing our critical attention on revision and correction, if required.

Errors, Missing Words & Challenges

Although the difficulties of reading a medieval text are not far from our research field, creating a clean transcription of the manuscript with AI created obstacles different from our previous experiences. Paris Bibles are separated into two columns and nearly every line is full of abbreviations.

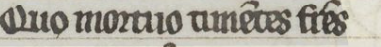

Typically, the resemblance of the letters was tough to determine straightforwardly. Among the lines most difficult to identify were the letters M, T, I, and R. Here are two examples where parsing the vertical strokes of the hand was particularly difficult. :

Figure 2: The translation of Transkribus HTR-1, Quo mortuo timentes fratres

Figure 3: The translation of Transkribus HTR-2, absque parvulis et gregibus atque

While we were attempting to review the text word by word, we noticed that some words that there are slight variations in word order and omissions compared with the edition of the reference Latin Bible Obviously, we ought to keep in mind the Bible written by hand would result in scribal fatigue. In those moments, it could be easy to forget a word or to miss a line.

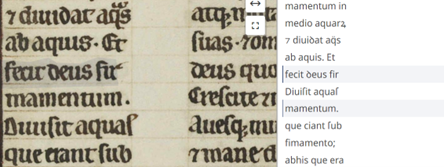

Other problems in line order were sometimes caused by Transkribus itself. We observed that in the sentence has been read by the HTR text with a reversal of two lines . As in the figure 7 appears “mamentum” staying under “Duisit aquas”.

Figure 4: Error

Word counts with Voyant Tools

We analyzed the transcription of our folio from Genesis in Arrau MsWettF 11 to get a general idea of the most frequent abbreviations.. Our corpus has been formed with 335 words and 277 unique word forms. The most frequent words in the corpus are eſt (8); in (7); cū (6); me (5); ut (4) as shown in the word cloud below:

Figure 5: Word frequency of the first folio of Genesis, Aarau MsWettF 11

It was obvious that unlemmatized diplomatic transcriptions such as those we created have some drawbacks; egẏptuſ and egẏptū appear in the wordcloud as separate words.

On the folio we studied most every line has been written with various abbreviations, in particular, at the end of the sentences. We cannot conclude, however, in general why so many abbreviations were used in manuscripts. There are several possibilities that occurred to us during the workshop. Of course, abbreviations save us time when typing as they are faster than writing the whole word. Also, it uses less space on the page, which is a significant point because parchment is expensive, when we think about the physical conditions of medieval times. From what we experienced hands on, we cannot see general rules for abbreviation usage. It may depend on the geographical areas, the abbeys or habits of individual scribes.

Conclusion

Using Transkribus in the context of medieval manuscripts foregrounds the importance of many aspects of material culture: codex construction, human transcription errors, even scribal habits in the collective record of our written civilization. Furthermore, automatic transcription in the humanities is allowing us to explore with greater ease the unedited, handwritten historical archives. With the realization of the roles of humans in text production, AI algorithms definitely provides a new way to explore elements of the forgotten past.

In conclusion, working with Transkribus has been an unusual adventure in understanding the relationship between manuscripts and transcription. Participating in the PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon allowed us to discuss medieval manuscript culture in a broad context. Moreover, it opens the door to so many new questions to be explored. How many people were involved in the creation of the manuscripts? How much time did they spend on these texts? Is the Paris Bible indeed the inspiration for the Gutenberg’s Bible? These questions are waiting to be answered through additional research.

Team

Serhat Açar and Elia Coulot.

Suggested citation

Açar, Serhat, Coulot, Elia. (22 June 2023). PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon: Aargauer Kantonsbibliothek, MsWettF 11. Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.