PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon #5: the case of Beinecke Ms 387

PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon: Beinecke Ms 387

This blogpost was written in the context of the Paris Bible Challenge which took place in Besançon, France in January 2023.

We examined the document known as Yale University Library, Beinecke Ms 387, a 13th century Bible made either in England or Northern France. What follows is our team’s observations and comments on the “Beinecke Ms 387” Bible and the challenge.

Together with our teammates, we set out to correct the transcription of the beginning of Genesis. We optimistically attempted multiple pages, but we ran into several issues and discussing possible solutions amongst ourselves delayed our task. Ultimately we were only able to complete the transcription editing for Transkribus page 5, the first recto and verso of Genesis, as well as the first column of the following page. Nonetheless, at the end of the correct-a-thon the modest contribution of the entire group’s transcriptions were added to the ground truth, helping the model lower its error rate by about 2%.

The first challenge we faced was making sense of the Bible’s words, letters and punctuation marks. Understanding the passages was no easy feat but between the PBP Transcription Guidelines and an online edition of the Vulgate Latin Bible for reference we were able to decipher the scribe’s hand.

Observations about the Scribe

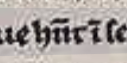

However practical and useful the guidelines were in the beginning, we soon realised that these weren’t entirely reliable. The more lines we corrected, the more we began to note the amount of inconsistencies within words that didn’t respond to any given rule or reason in their spelling choice. An example of this happens for the word secundum, which appeared numerous times in the text, but was abbreviated or written in different ways, seemingly at random. The word could appear as ſcꝺ̄m, but could also sometimes be abbreviated as ſcꝺ̄ō, but rarely, if at all, was secundum ever entirely written out.

|  | Figure 1: Example of ſcꝺ̄ō within the text of Beinecke 387. | |-|-|

| Figure 1: Example of ſcꝺ̄ō within the text of Beinecke 387. | |-|-|

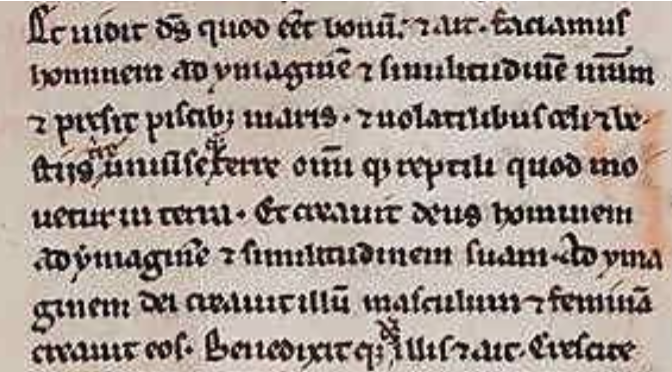

This was also the case for the word deus, which was generally abbreviated as ꝺs̄ with a macron between the first and second letter. In some instances, we noticed that the full word would be written out with no indication why sometimes it would be abbreviated and sometimes not.

|  | Figure 2: Example of ꝺs̄ within the text. | |-|-|

| Figure 2: Example of ꝺs̄ within the text. | |-|-|

This begs the question of why we find a variety in abbreviations for the same word, and why is it that on a single leaf, there appears to be no logic behind the decision of which abbreviation gets used. One could hypothesize that the choice of abbreviations is related to the remaining space on the line. Or perhaps it could simply be because such abbreviations appeared this way in our scribe’s reference Bible, and he was just copying what was in front of him. Either way, the scribe who transcribed the Beinecke MS 387 Bible was consistently inconsistent in his abbreviations and in his refusal to create uniformity throughout, which made the transcription that much more an interesting challenge.

While training for scribal work and copying existed in monasteries, as far as we know, no standard was put into place to regulate abbreviations. While there are a few that seem to be universal in Paris Bibles, like the macron over a letter to replace an “m” or an “n” and to combine letters which turned words like habent into hn̄t (Fig. 3), some of the abbreviations the copyist for the Beinecke MS 387 appear to be less common. Among these uncommon abbreviations that were recurring in our Bible were gᔆ, which stood in for the word igitur (Fig. 4) and qͦ, which replaced quod (Fig. 5). Furthermore, in the 39th line of the second column of the first page, there is an abbreviation which we could not confidently decipher. We believe this word to represent eius (Fig. 6) but because of the low quality picture, occurrences like this one became like this one were difficult to interpret, especially since our scribe was not the most consistent nor the most clear to begin with.

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 3: Example of macron usage to condense words in the text. | Figure 4: Example of quod abbreviation. | Figure 5: Example of igitur abbreviation. | Figure 6: Example of quod abbreviation. |

Other inconsistency issues we noticed during the correction process occurred with capitalization of words at the start of new paragraphs. Our scribe would illogically capitalize words when there was no new section, or sometimes even use capitals in the middle of a line, as happened often with the word et in the example below, found in page 5, column 2, line 5 of Beinecke 387. In other cases, capital words are more clearly more evident thanks to the use of color.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 7: Example of et capitalization within the text. | Figure 8: Example of colored capitalization within the text. |

Other times, the scribe would make mistakes such as altering the order of the words or adding others (we corroborated this by following a Vulgate Latin version of the Genesis text(https://vulgate.org/ot/genesis_1.htm)). They would also erroneously or purposefully omit words and in some cases they would add them above the line where they originally should have been. Other times, they crossed out a word or even wrote them twice because the first attempt had come out illegible, as was the case with this repeated word tertius in the last line of page 1, column 1, paragraph 3. Although the word wasn’t crossed out, the scribe wrote it down a second time, perhaps thinking the first attempt wasn’t visible enough.

|  | Figure 9: Example of tertueſ/tertius within the text. | |-|-|

| Figure 9: Example of tertueſ/tertius within the text. | |-|-|

Transkribus in Action

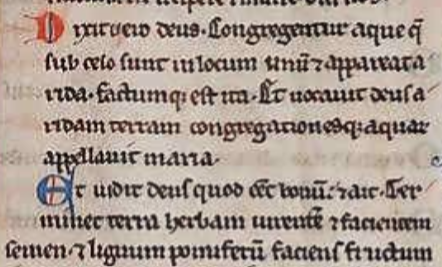

Even though we’ve been mainly focusing on errors or mistakes either made by the scribe or Transkribus, it’s also worth mentioning that the transcription tool did get it right most of the time. Looking at the overall picture, the accuracy of the digital tool was quite impressive, and following its transcription helped us gain a better understanding of the original texts whenever we had doubts or ran into a particularly difficult word to decipher. An example of this is the latin word facientem, which by the looks of it seemed hard to understand. But with the help of Transkribus’ text copy, it was easier to make sense of the scribe’s handwriting.

|  | Figure 10: Transkribus page 5, paragraph 3, line 2. | |-|-|

| Figure 10: Transkribus page 5, paragraph 3, line 2. | |-|-|

However, we also noticed when the machine transcription made several repeated mistakes, particularly in the case of words that looked similar. Repeating machine transcription mistakes:

| c = t | ct = d | e = c | rt = u | c = i | rn = m | h = b | H = N | s = o | |—|—|—|—|—|—|—|—|—|

Recommendations

The usage of ꝫ to stand for “ue” and often used with q to stand for que as indicated on the Guidelines is reflected in our experience with this manuscript. However, the scribe’s handwriting gives that ꝫ a variety of appearances and occasionally appears as a semi-colon. Adding an example or two of the variety of ꝫs would be beneficial to any future crowdsourced transcription work.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Figure 11: (qꝫ) appearing as (q;). | Figure 12: (qꝫ) appearing as neither. | Figure 13: (qꝫ) appearing as (qꝫ). |

The reversed question mark (⸮) is also present in the Guidelines and said to stand for the usual question mark. In this manuscript, the ⸮ shows up repeatedly and does not appear to represent any word or punctuation. It would be a good idea to note that in the Guidelines.

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Figure 14: ⸮ clearly depicted. | Figure 15: ⸮ appearing as more of a “F”. | Figure 16: ⸮ appearing as more of a “E”. |

Conclusion

To conclude, we learned a lot about how manuscripts and AI can interact together during our hands-on challenge week with the Paris Bible Project. Before starting the Correct-a-thon, the abbreviations we saw in the manuscripts at Besançon’s municipal library weren’t decoded for us and we didn’t yet have resources on how to decipher them. But thanks to our participation in the project, we were able to experience up close the variance so characteristic of medieval manuscripts.. A new door has opened for us in the sense that we are now better equipped to understand and interpret medieval Latin manuscripts. This experience was a great help that furthered our understanding of the creative process behind these beautiful, ancient items.

This challenge also represented the first time we worked with AI during this master, and with this, we were really able to understand how a model for transcribing manuscripts can evolve with the submissions of pages. It helped us realize the importance AI research and transcription tools can possess when working with medieval manuscripts and other rare and ancient books, as the paleographic task that these documents command is quite heavy for non-computer assisted projects, especially for a document with as many pages as the Bible! It was truly shocking to see how efficiently and consistently the model was able to understand the imperfect calligraphy and poor picture quality of the Beinecke MS 387 Bible.

Team

Lucia Sol Bezzecchi Petroff, Amanda Robin Hemmons, Alexandre Keyes.

Suggested citation

Bezzecchi Petroff, Lucia Sol, Hemmons, Amanda Robin, and Keyes, Alexandre. (15 June 2023). PBP Challenge Besançon: Beinecke Ms 387 Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.