PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon 2023 #4: the case of Stanford Ms 23

PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon: Stanford Ms 23

This post was written in the context of the Paris Bible Challenge which took place in Besançon, France in January 2023.

The main goal of the correct-a-thon was to reflect on the use of Transkribus with abbreviated medieval Latin Bibles and to improve the quality of the Paris Bible Project ground truth data . In order to achieve these goals, participants were invited to check and, if necessary, supplement and correct the automatically created computer transcriptions. All transcriptions were made with Transkribus software using handwritten text recognition (HTR) technology from digitized copies of manuscripts’ pages. Our team worked with the Stanford 23 manuscript. Below we elaborate on the process of work and the obtained results.

About the manuscript

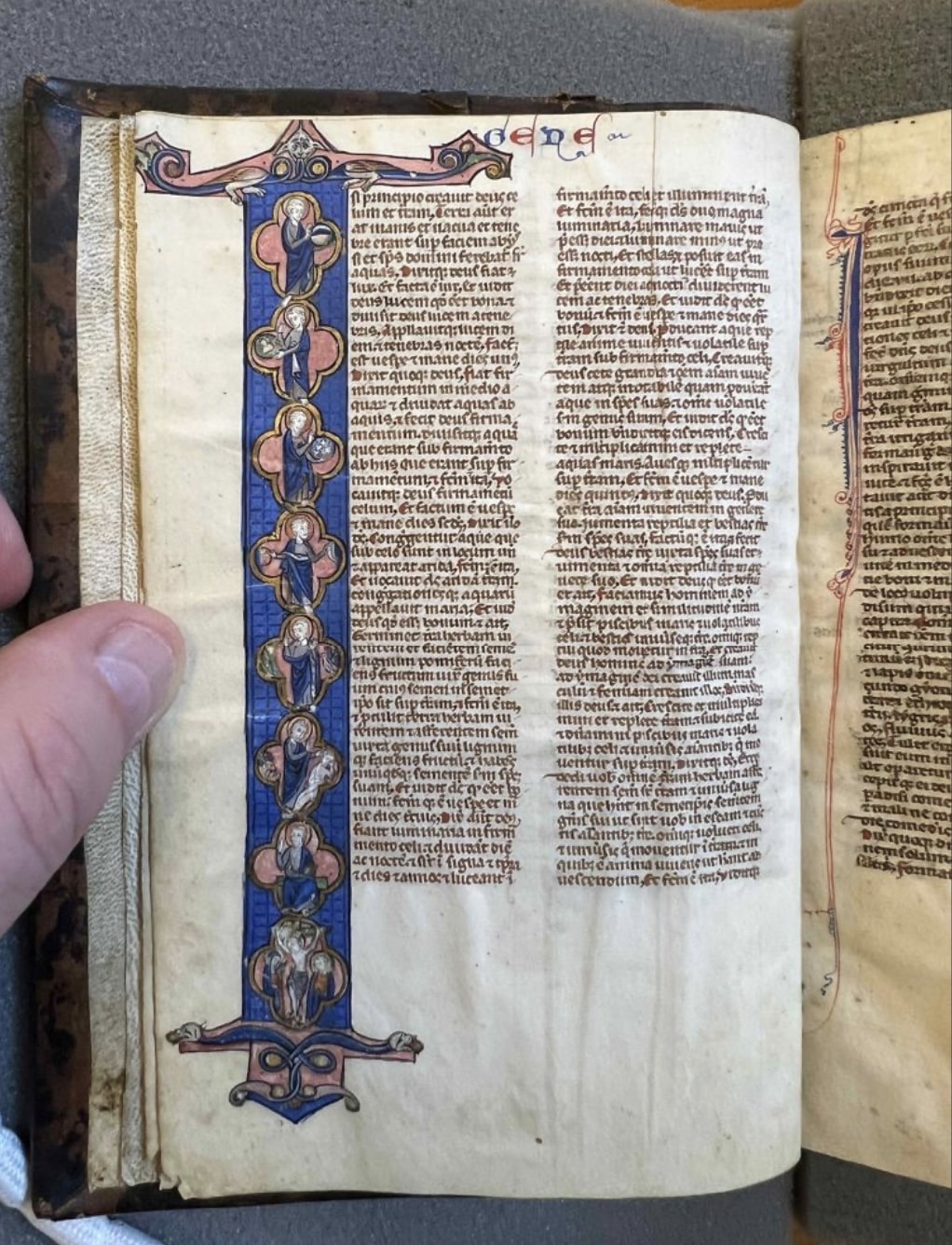

We worked with photographs of Stanford Ms 23 manuscript pages taken by David J. Wrisley at the Stanford Library. The entire manuscript has not been digitized but several pages are available online at the Stanford libraries website. The manuscript we believe was made in Paris in the mid-1250s, small in size (148 x 96 mm) with extremely thin pages. The text is written in brown ink in a minuscule bookhand in two columns, 48 lines per page. The first letters of Genesis and Exodus which we were able to work with are richly decorated. Capital letters are accentuated with red. The first letters of the chapters are in red and blue. The title of the book (Genesis or Exodus) is also in the same colors at the top of the page. A few marginalia were found in these sections.

Figure 1: First page of Genesis from the manuscript.

Working with Transkribus

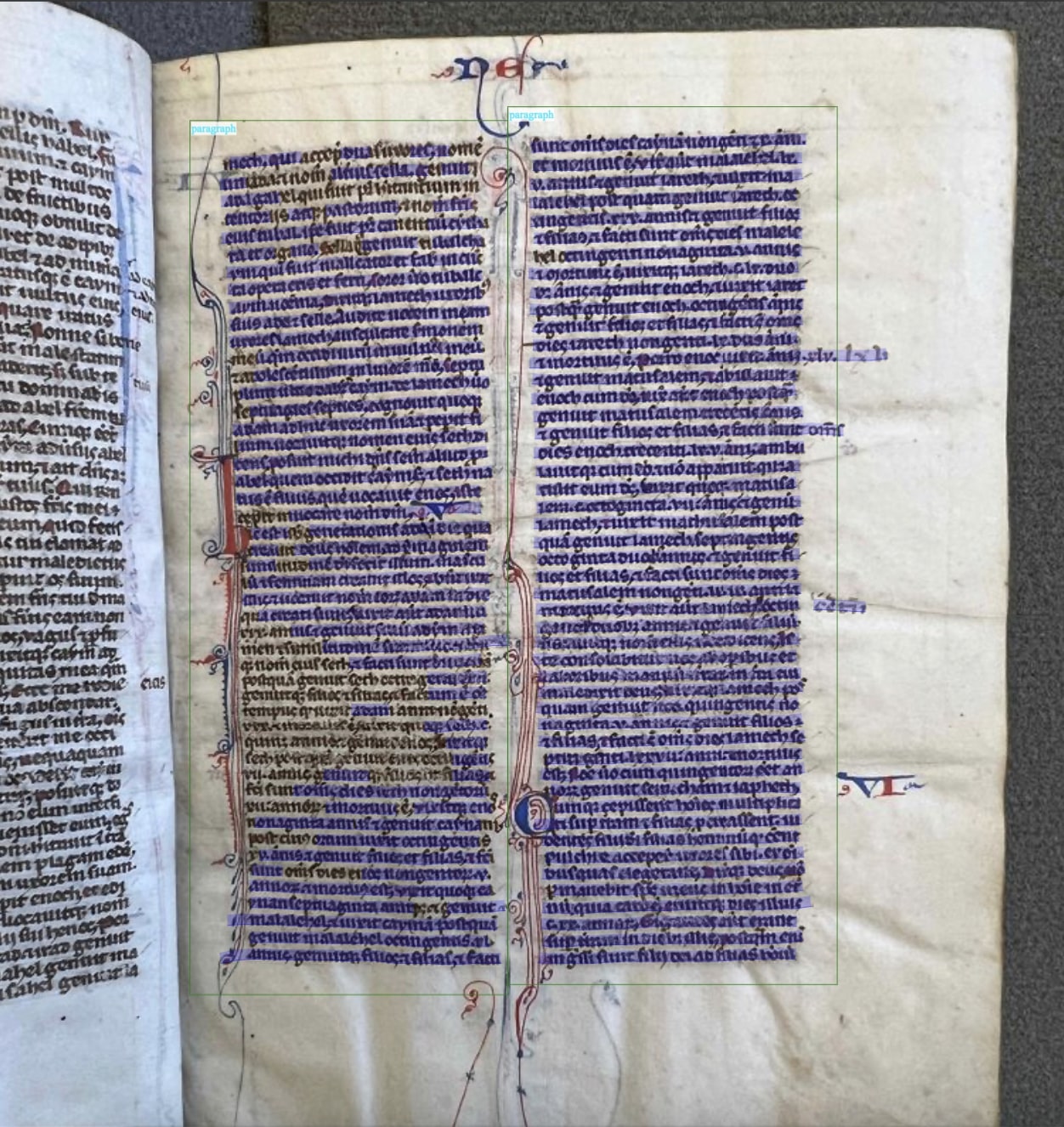

All the transcription work was carried out on the Transkribus website. Inside Workdesk, an account dashboard, folders with copies of documents can be created. Our team’s folder contains 104 photos of manuscript pages. Each page can be studied in three modes. “View” is a copy of the document and its transcript, in “Text” you can correct the transcript line by line, in “Layout” you can see how the service has recognized the text. All of the work to correct the transcription was done in “Text” mode. The pages that were ready for correction have the status “In Progress”, and those that were checked are marked with the “Done” status.

What did we notice while working on the manuscript using Transkribus?

- Due to the fact that the Paris Bible Project used its own model (for this correct-a-thon, PBP 2.1), trained for Transkribus on different manuscripts, the overall quality of transcribing texts is quite good.

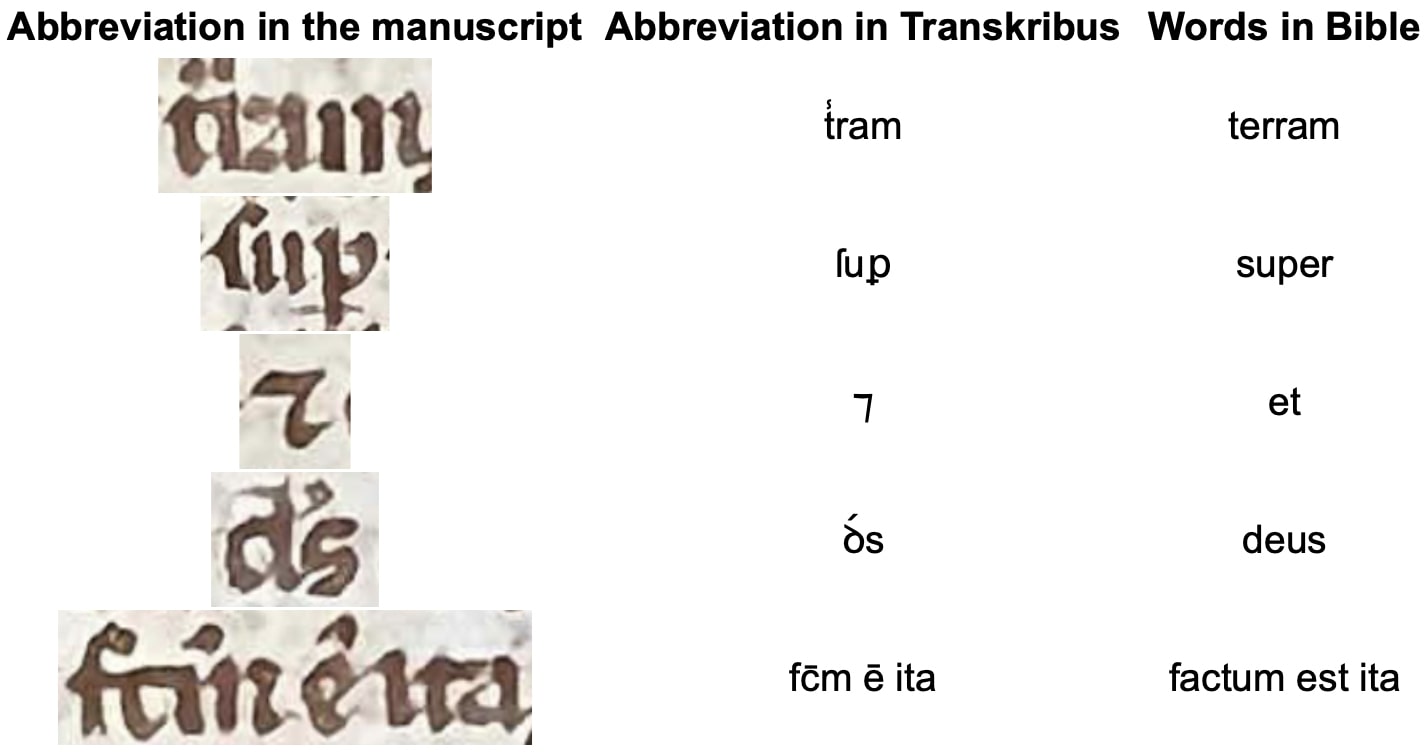

- AI is good at recognizing scribe’s handwriting, abbreviations and words that are difficult to read for human eyes. See this article about how AI can read bad scans.

Figure 2: Example of good text recognition.

- The thin pages with very thick writing, creases on pages, and digitized photos taken on the phone (without using special equipment) sometimes caused poor recognition of whole chunks of text. In addition, the spacing is sometimes too small to be noticed, the words seem to be combined together.

Figure 3: Example of text recognition with Transkribus. The words not highlighted in blue are unrecognized.

- Blank lines appeared on some pages in the transcription that do not correspond to anything on the copy of the manuscript page.

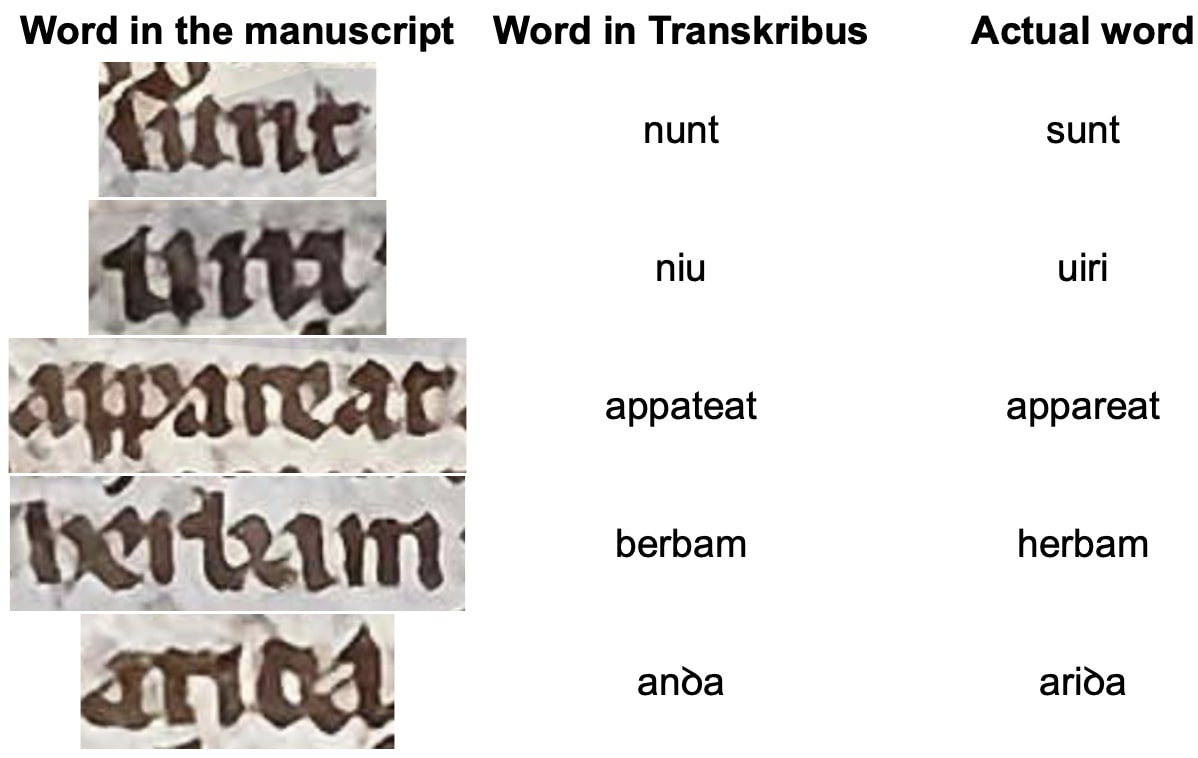

- Sometimes the AI confuses the letters t and r, b and h, ui and ni,mand n because of the script features.

Figure 4: Example of mistaken recognition with Transkribus.

- AI picks up the difference between ꝺ and a standard d very well.

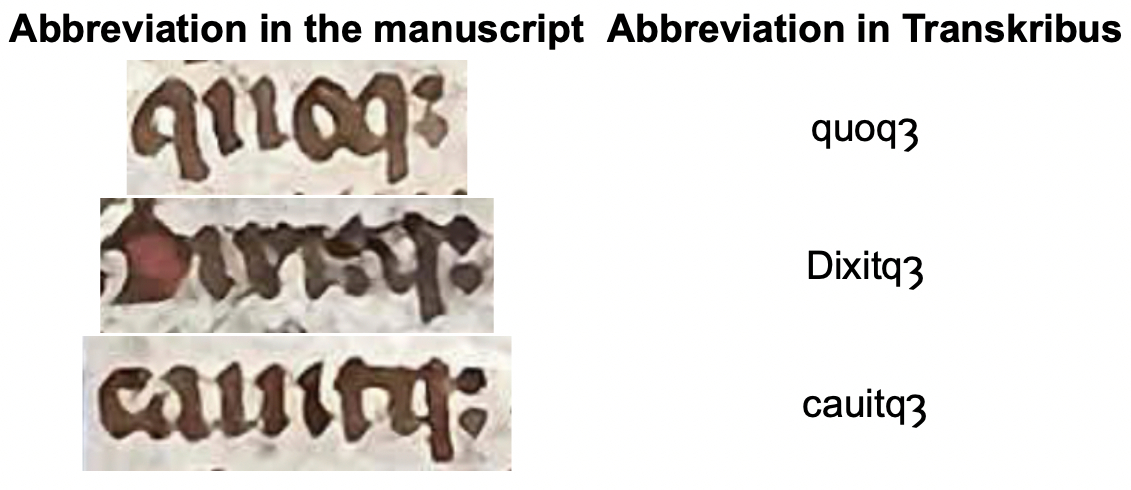

- Quite a curious example with the recognition of the abbreviation ꝫ. With 100% accuracy Transkribus translated it correctly, although in many places of the manuscript it looks more like a ; sign. The model was trained on manuscripts in which this abbreviation is actually written by the scribes that way. On the one hand, the AI transcription is perfectly correct; on the other hand, it differs from the scribe’s handwriting.

Figure 5: Example of the abbreviation ꝫ used for ue letters at the end of words.

Although we did not have time to check all the pages, some conclusions about the quality of the transcription can still be drawn from the available data. The most unexpected part of the research is how the AI manages to recognize difficult to read words and abbreviations without errors, but at the same time misses entire lines of readable text. Perhaps it is the phone photos and if the pages had been digitized with professional equipment, this situation would have been avoided. Nevertheless, we cannot say that photos from the phone are not suitable for transcription at all, because a large amount of text was transcribed very well.

Working with Stanford Ms 23

We would like to elaborate on the manuscript and the features of the scribe’s hand that we managed to discover during the correct-a-thon. What we were able to observe during our study:

- Because of the small size of the manuscript we expected to see a large variety of abbreviations, the use of which would be structured and logical. However, despite the presence of abbreviations, it cannot be claimed that their use by a scribe is always subordinated to clear rules. For example, using different abbreviations of the word super on adjacent lines of text.

Figure 6: Example of abbreviations for super.

- The absence of consistency in abbreviations is often seen in the following words in different declensions: terra, deus, factus, minus.

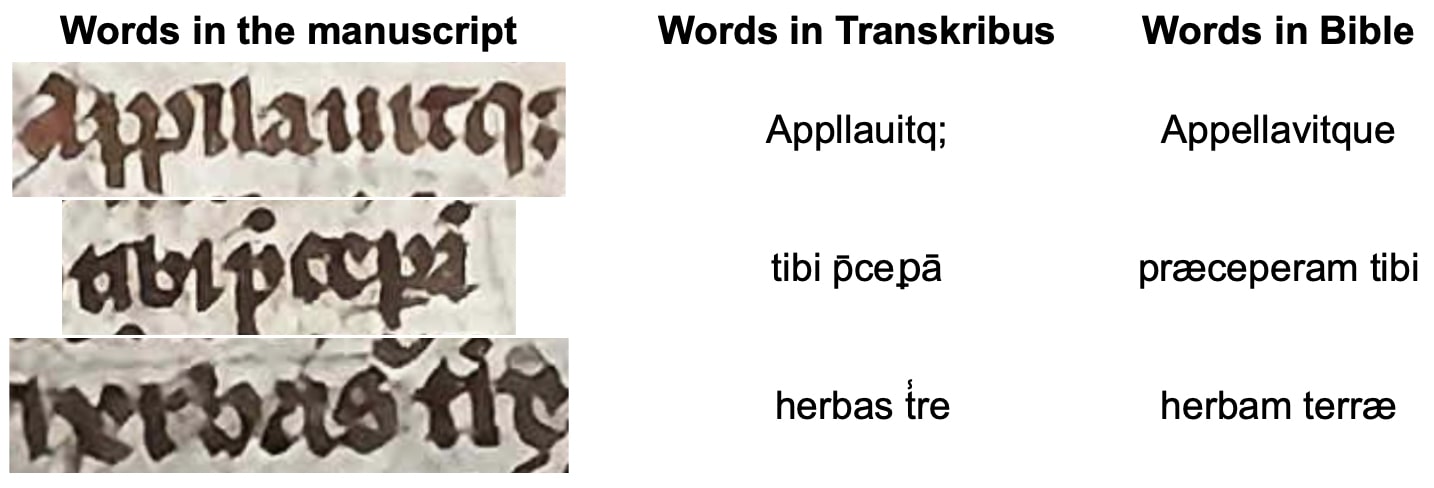

- Ongoing comparison with the edited text of the Vulgate revealed differences in spelling, omissions of several words without losing the meaning of the sentence and rearrangement of words.

Figure 7: Examples of misspelling and word rearrangement.

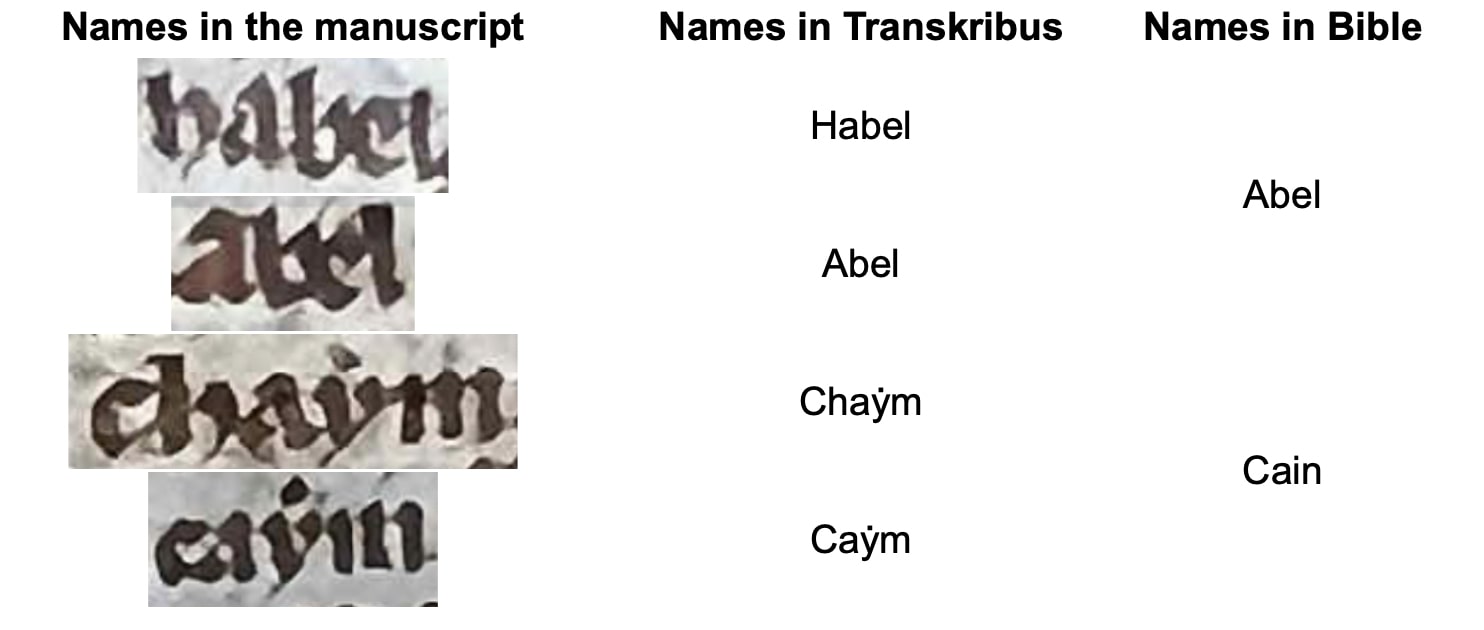

- It’s interesting to observe how the scribe spells proper names. Abel in the first two occurrences in the text is written as Habel, Cain – as Caym (and once as Chaym). The example of the spelling of Cain’s name is noteworthy because it is characteristic of the Gaelic tradition. And this can confirm the region of origin of this manuscript.

Figure 8: Examples of names’ spellings.

In Review

Transkribus

- During teamwork it turned out that the Transkribus interface works slower than during individual work and sometimes even may not save the changes made. Perhaps Transkribus should provide a way to optimize the process of teamwork in the browser.

- The browser version does not provide auto-save.

- The line highlighting (in light blue) in Transkribus is too dim and often hard to discern.

Transcription

- Although in some cases AI pushes us to use a particular abbreviation (i.e., macron, ꝫ), we must focus first on what we see in the manuscript. Is the automatic transcription really correct or is it the result of model overfitting (see blog post for Beinecke 1100 for an explanation on overfitting)? We had to make such micro-decisions quite often when working with the Transkribus.

- The process required constant discussion of various decisions made to ensure the accuracy of the transcription. How accurately did the software translate each abbreviation? Which Unicode character is best for each abbreviation? These questions on the one hand prompted general thoughts about AI models and their biases, and on the other forced one to look closely at each character.

- Reading the manuscript quickly became reading the scribe’s handwriting and trying to understand his logic and his intentions. Close reading took on the very literal meaning of looking into the particular letters written by the scribe.

- The collaborative work and the process of collating the texts of the manuscript, the transcription, and the online version of the Bible made it possible to look at the work from different perspectives. It was truly a challenging and fascinating adventure.

Future opportunities

- By having a large number of transcribed pages from various manuscripts, the Paris Bible Project team will be able to retrain the model, hopefully leading to more accurate text recognition.

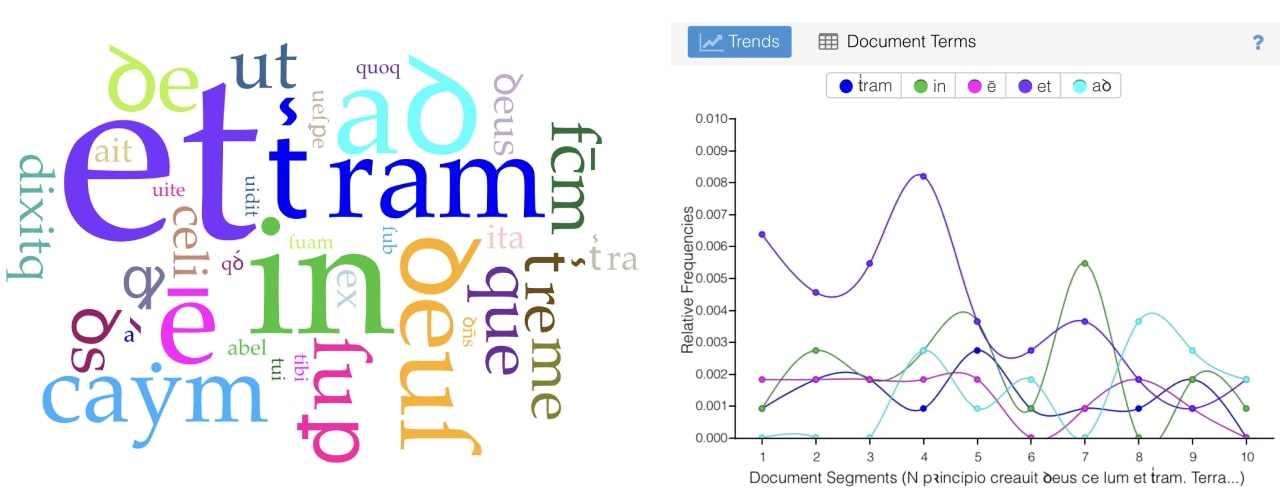

- By transcribing many pages it will be possible to do textual analysis of a single manuscript as well as to compare multiple copies. This will make it possible to find common patterns in the use of abbreviations and fundamental differences between writing styles, to take results of HTR and use it in broader context: statistics, words diffusion, patterns of abbreviations distribution throughout the manuscript etc. Obviously, a textual analysis done on just a few pages cannot be used as a scientific argument, but below is an example of a word cloud and a trend in word usage.

Figure 9: Examples text reading and analysis of two pages from Genesis using the Voyant tool.

During the week-long correct-a-thon our team:

- learned how to work with tools like AntConc, Voyant, and especially Transkribus.

- gained real experience in transcribing a manuscript.

- got to know the possibilities of AI application in digital humanities.

- visited the Municipal Library of Besançon, where we saw manuscripts similar to the one we were working with.

- contributed to the quantity and quality of ground truth.

Team

Benedicta Aurthur, Anna Chemisova, Marie Noirot.

Suggested citation

Arthur, Benedicta, Chemisova, Anna, and Noirot, Marie. (08 June 2023). PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon: Stanford Ms 23. Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.