PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon 2023 #1: the case of Beinecke MS 1100

PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon 2023: Scribal Differences and Abbreviation Ambiguities in Beinecke MS 1100

This post was written in the context of the Paris Bible Correct-a-thon which took place in Besançon, France in January 2023.

As part of the Paris Bible Correct-a-thon which took place in Besançon in January 2023 in collaboration with the Université de Franche-Comté, our aim was to correct part of the transcription generated by the software Transkribus for a selected number of pages within a given manuscript. Our team studied a 13th-century Bible, Beinecke MS 1100. Together, we managed to correct the transcription for three pages from Genesis (6v, 7r and 7v) as well as partially correct folio 9r. Below is an account of our findings.

Evidence of possible scribal differences

Having corrected three successive pages, we began to notice some variations in handwriting, for the most part very subtle, but enough to draw attention to the possibility of at least two different scribes’ involvement. Of course, it’s only a working theory and we would need to examine more material as well as develop more ground truth before making any definite claim, but for the purposes of this project, let’s assume that there were in fact two or more scribes writing these three pages.

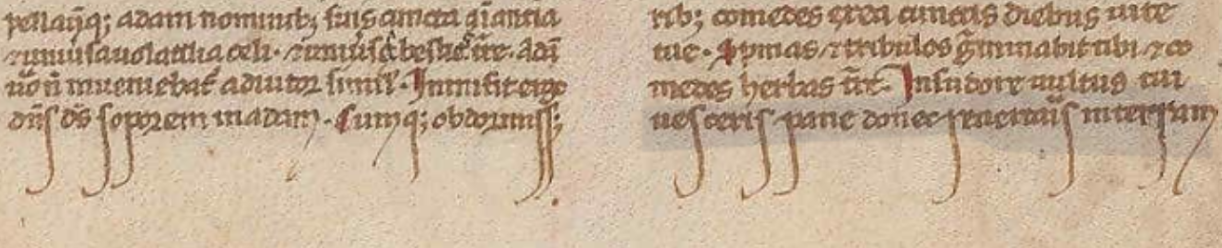

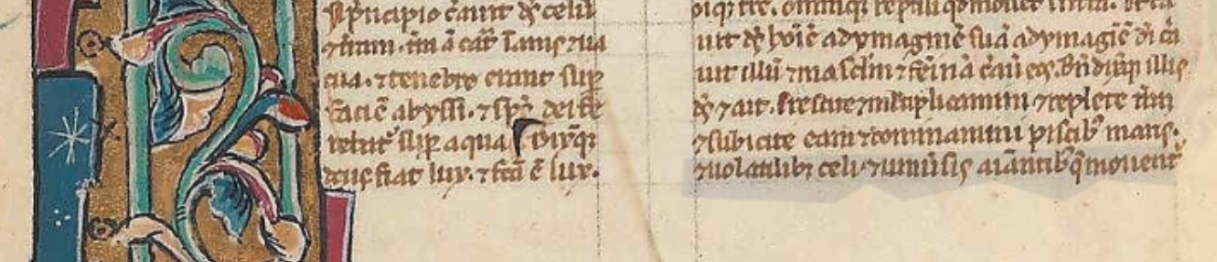

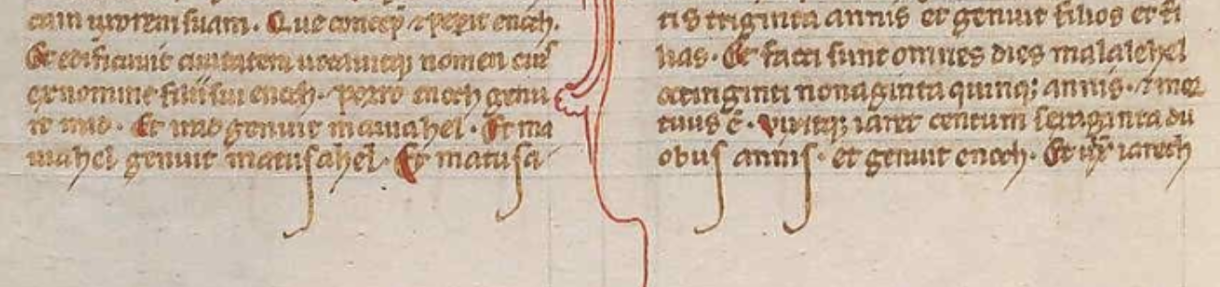

Regarding handwriting, one of the main differences we observed was in the stylization of the letters in the first and last lines of a column. On 7r, we can clearly see the ‘tails’ of the letters ‘s’ and ‘p’ (see Fig.1), elongated downwards, whereas on 6v, we observe the absence of any such stylized element (see Fig.2). Additionally, on 7v, the same descenders make a comeback (see Fig. 3). Are these examples of two different hands? Or did the scribe simply not want to add any more decorations to the already heavily illuminated first page of Genesis? Why do they appear again on 7v?

Fig.1: Example of descenders on the bottom line of Beinecke MS 1100, folio 7r.

Fig. 2: Example of “regular” letters on the bottom line of Beinecke MS 1100, folio 6v.

Fig. 3: Example of descenders in the bottom line of Beinecke MS 1100, folio 7v.

Note also how the handwriting appears more compact, the letters and ink more dense on folio 7r versus folios 6v and 7v. Once again, the difference is subtle and what appears as a different hand might in fact simply be the result of parchment and ink aging, but the question remains. The difference is particularly apparent when looking at the second column pictured in Fig.1 and 2; In Fig.1, the hand is heavier and the ink less defined than in Fig.2, where each letter is clearly outlined but the spacing between them is shorter.

Table of abbreviation ambiguities: examples of AI overfitting ?

| In the text | Composed of | Meaning | Usage | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “et” | et | “and” | Beginning of sentence | Written out fully |

| ‘⁊’ | U+204A | “and” | Middle/end of sentence | Often mistaken for ‘ꝯ’ |

| “ꝫ” | U+A76B | “m” | p. 11 section 1, l.6 | First time used in the text |

| “aīa” | U+0304 | “anima” | Compound letters | Macron can often compound letters ‘m’ and ‘n’ |

| ⁊ and ‘ꝯ’ | U+A76F | “and” | Mistaken for one another | AI overfitting issue |

| “gͦ” | U+0366 | igitur or ergo | Ambiguous | Meaning unclear from the information |

| ‘r’ and ‘n’ following each other | ‘r’ and ‘n’ | “m” | Gothic script density | Often mistaken for an ‘m’ |

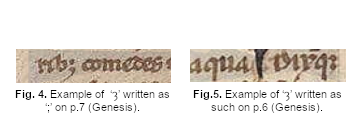

| ‘;’ | U+003B | “us” or “ue” | End of a word | Sometimes written as ‘ꝫ’ and sometimes as “;” |

| Superscript tilde | U+0303 | Above letters other than “t” | Occurs above letters such as “x” and “u” |

With regards to abbreviations, the most interesting observation we made by far has to do with the ambiguity surrounding the abbreviations ‘ꝫ’ and ‘;’. The unicode character ‘ꝫ’ is usually used, as described in the Transcription Guidelines, to denote the letter combinations ‘ue’ and ‘us’, often found right after the letter ‘q’. The unicode character ‘;’ stands for a semi-colon. In Genesis, in some instances, the two are used interchangeably: on 7r, the ‘ꝫ’ is written starkly as a ‘;’ (see Fig.4) but on 6v, in the first column, second to last line, it appears as a normal ‘ꝫ’ (see Fig.5).

This could be an example of ‘overfitting’, defined by IBM as follows:

Overfitting is a concept in data science, which occurs when a statistical model fits exactly against its training data. When this happens, the algorithm unfortunately cannot perform accurately against unseen data, defeating its purpose. When the model trains for too long on sample data or when the model is too complex, it can start to learn the “noise” or irrelevant information, within the dataset.

In layman’s terms, overfitting happens when a model is trained a little too well and is unable to recognise variations in data. In our case, when studying the three pages from Genesis in Beinecke MS 1100, we realized that the Transkribus model had been trained to recognize all ‘;’ as ‘ꝫ’. According to the ‘Five Principles’ of manuscript transcription outlined in our guidelines, we chose to view this as a sign that the semi-colons on 7r were in fact stylized ‘ꝫ’, judging by their place within the sentence and the modern latin translation of the Vulgate.

Concluding remarks

Working with old manuscripts like the Beinecke MS 1100 pushes us to consider another question, perhaps more problematic: should we aim to modernize the Latin script from medieval Latin to a more readable form to the lay reader or not? According to the principles laid out for the correct-a-thon, the choice was made not to stray from the original text, even if the Latin employed by the scribes is almost unintelligible to the modern reader without the help of a modern Latin translation of the bible. But in the context of the preparation of the manuscript itself, the specific use of Latin and its specific abbreviation conventions can also participate in telling the story of the text.

By far the most compelling aspect of this correct-a-thon was the way it forced us to come face to face–for lack of a better expression–with a nameless, faceless scribe writing centuries ago, taking months to finish one single manuscript. In comparison, our modern approach to writing and reading appears so very rushed and artificial. When reading a book through printed text, whether that be in a physical or digital form, discerning the “hand” of the writer takes on a completely different meaning. The hand no longer refers to handwriting, but to tone or language; to figures of speech and thought processes.

The hand of the scribe becomes apparent in the human errors, such as the forgotten abbreviation on the word “eem”, usually written with a macron on ‘e’ and yet shining here by its absence. (See folio 7r, section 2, l.29) Or in the decision-making process of using one abbreviation instead of another, such as using an apostrophe instead of a macron.

This is not to say that we should aim to emulate or go back to a time where manuscripts were precious precisely because of that hand–that rarity factor–but it is nonetheless a thought which bears some consideration. How can we use those transcriptions to uncover at least part of the scribal hand underneath the text? How can we link monasteries, scribes and manuscripts together to give back names and faces to manuscripts which have had none for centuries?

Team

Gauri Bhagwat, Alice Fournier and Robert Lloyd.

Suggested citation

Bhagwat, Gauri, Fournier, Alice and Lloyd, Robert. (12 May 2023). PBP Correct-a-thon Besançon: Scribal Differences and Abbreviation Ambiguities in Beinecke MS 1100. Paris Bible Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040632

This post is published with a CC BY-SA-NC 4.0 International license.